that was in part motivated by an article in the NYT written by Yergin at CERA which essentially argued that there is no problem, and that somehow technology will save the day.

This morning there was a story posted at:

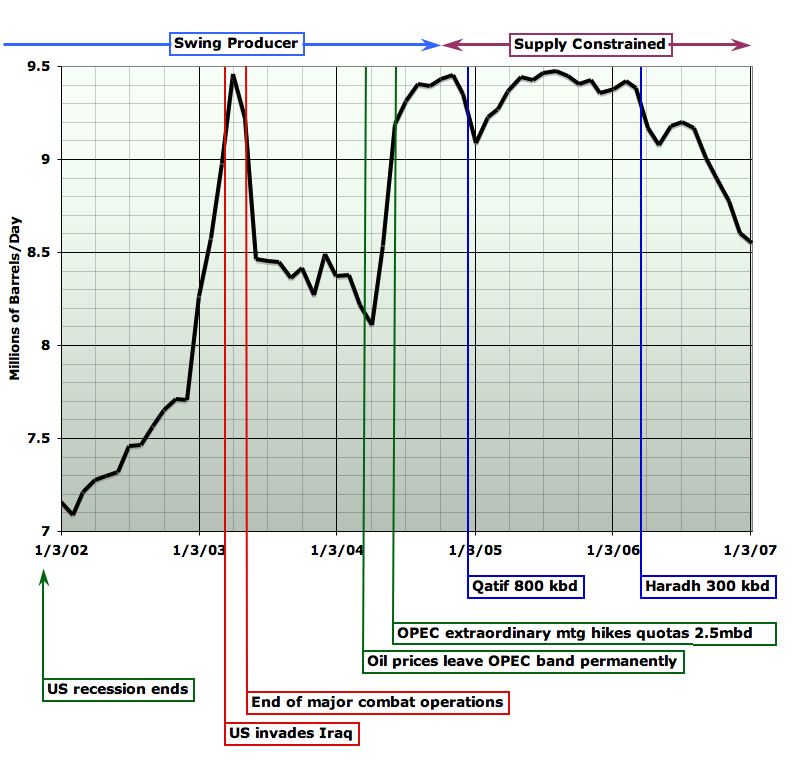

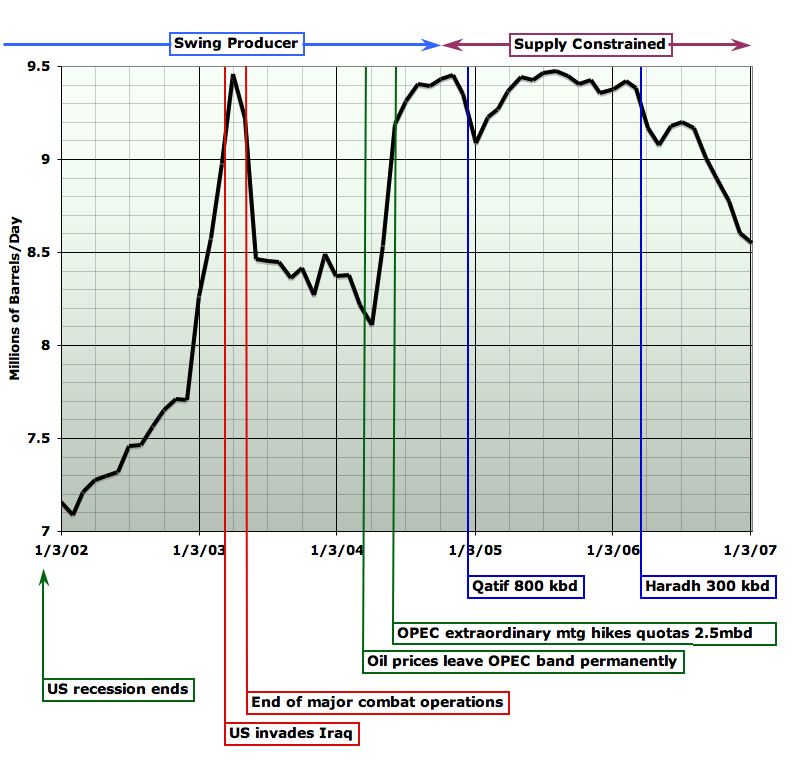

that discusses oil production for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). There is more than adequate evidence that KSA production declined by 8% last year - the question is why. Was it voluntary for one reason or another, or have they peaked, and they are simply no longer able to maintain production levels.

Unfortunately KSA isn't very forthcoming with real data as to how their individual oilfields are doing, so the analysis that was done in the article at theoildrum is essentially based upon the information that we do have at hand. The argument that is made is that since sometime in 2004, all of the spare capacity that they have used in the past in order to control prices is now gone.

There really isn't any point in my repeating the arguments that was made in the article at theoildrum - the author spends a long time developing his arguments. Given that the information that he used to make the argument is somewhat indirect, there is of course the possibility that there are other explainations for why KSA has been cutting production, and the article addresses these towards the end.

The obvious question would be what this all means for the rest of us. KSA by themselves only produce about 10% of the world total. In 2006, the KSA production dropped about 8% or so - this by itself only amounts to a 1% decline in total world production in 2006. Of greater concern is that some of the other large oilfields in the world are also reaching an age where the production is declining rather than increasing. Into this category I would place the Burgan field in Kuwait and the Cantarell oilfield in Mexico - both of which have entered a state of terminal decline, and both of which are listed among the largest oilfields in the world. There are other well known oilfields that are in a similar state - it isn't just this handful of super-giants that are in trouble.

In relation to the Peak Oil theory, other forms of hydrocarbons, such as oil sands and oil shake aren't strictly relevant. By this I mean that they are sufficiently different from regular oil that the production methods and other potential limitations are entirely different from the methods that have been used in the past to extract liquid oil, and if the methods are different, then the economics and the economies of scale are also different (or for that matter even the question of the *ability* to scale up to the point of producing meaningful quantities of oil).

Could new technologies be used to boost production of some of the older oilfields? Perhaps, but the existing oilfields have already made use of all of the existing technologies for coaxing oil out of the ground. Folks like Yergin like to wave the word "technology" around, but for that argument to be believable, it helps to be specific about exactly what types technologies are being talked about here. Once we get into specifics, we can start to evaluate each one on its own merits to see whether the ideas really make sense or not.

If one wanted to arrest declines in existing oilfields, we would need something sooner rather than later. Holding out hope for some yet-to-be-discovered technology isn't a proper way to develop sound public policy.

This is a huge topic, of course, and in order to avoid having to write a book, I have deliberately tried to restrict discussion specifically to the oil that we pump from the ground and not get into questions of any of the alternatives.