http://www.aps.org/energyeffic...

http://www.aps.org/energyeffic...

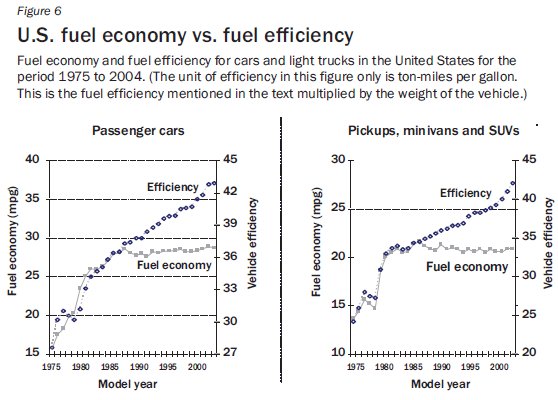

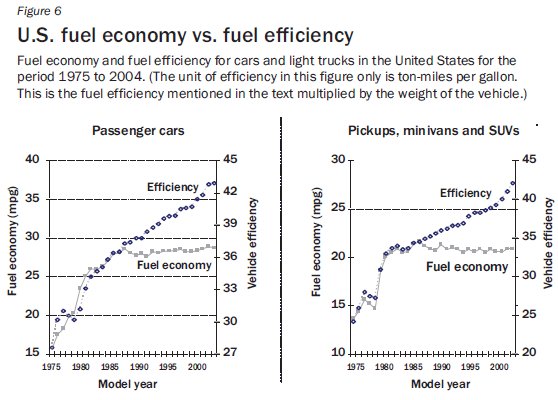

Here is one point - that overall vehicle efficiency has continue to increase, but those gains have been squandered in order to make heavier vehicles.

The implication is that simply by scaling down and reducing vehicle weight, that fuel efficiencies of nearly 40mpg are possible with no new technology.

This report discusses all energy use, and not just vehicle efficiency. Things like buildings, LEED, electricity consumption, plug-in hybrids (and the demands that this would place on the grid) are all mentioned.

Summary of Recommendations 1. The federal government should establish policies to ensure that new light-duty vehicles average 50 miles per gallon or more by 2030.

2. The federal government's current transportation R&D program should have a broader focus. A more balanced portfolio is needed across the full range of potential medium- and long-range advances in automotive technologies. Increased research is needed in batteries for conventional hybrids, plug-in hybrids and battery electric vehicles, and in various types of fuel cells. This more balanced portfolio is likely to bring significant benefits sooner than the current program through the development of a more diverse range of efficient modes of transportation, and will aid federal agencies in setting successive standards for reduced emissions per mile for vehicles.

3. "Time of use" electric-power metering is needed to make nighttime charging of electric vehicle batteries or plug-in hybrid vehicle (PHEV) batteries the preferred mode. Improvements in the electric grid must be made in order to handle charging of electric vehicles if daytime charging is to occur on a large scale or when the market penetration of electric vehicles becomes significant.

4. Federally funded social science research is needed to determine how land-use and transportation infrastructure can reduce vehicle miles traveled. Studies of consumer behavior as it relates to transportation should be conducted, as should policy and market-force studies on how to reduce vehicle miles traveled. Estimation of the long-term effects of transportation infrastructure on transportation demand should become a required component of the transportation planning process.

5. The federal government should set a goal for the U.S. building sector to use no more primary energy in 2030 than it did in 2008. The goal should be revisited at 5-year intervals in light of the available technology and revised to reflect even more aggressive goals if they are justified by technological improvements.

6. To achieve the 2030 zero energy building (ZEB) goal for commercial buildings - replacing fossil fuels with renewables and reducing energy consumption by 70 percent relative to conventional building usage - the federal government should create a research, development and demonstration program that makes integrated design and operation of buildings standard practice. The federal government, state governments and electric utilities should carry out the program co-operatively, with funding coming from all three entities.

7. Any green building rating system, such as the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Green Building Rating System, should give energy efficiency the highest priority and require reporting of energy consumption data.

8. The federal government should sharply increase its R&D spending for next-generation building technologies, for training building scientists and for supporting the associated national laboratory, university, and private sector research programs. Specifically, funding for building R&D should be restored to its 1980 level - $250 million in 2008 dollars - during the next 3 to 5 years from the current level of $100 million. At the end of that period the buildings program should be reviewed carefully to determine (1) how much continued federal funding will be needed for the program to reach its goals; and (2) which parts of the program are ready to be shifted to the private sector.

9. The existing demonstration program for construction of low-energy residential buildings, along with associated research, should be expanded.

10. The Department of Energy should develop and promulgate appliance efficiency standards at levels that are cost-effective and technically achievable, as required by the federal legislation enabling the standards. The department should use a streamlined procedure to promulgate the standards for all products for which it has been granted authority to do so.

11. The federal government should encourage states to initiate demand-side management (DSM) programs through utility companies, where such programs do not exist. Such programs, in which a central agency (often a utility company) assists customers in becoming more energy efficient, have proven cost-effective. The federal government could provide rewards to states that have significant and effective DSM programs and disincentives to those that don't.

12. Energy standards for buildings, such as the standards promulgated in California, should be implemented nationwide. States should be strongly encouraged to set standards for residential buildings and require localities to enforce them. The federal government should develop a computer software tool much like that used in California to enable states to adopt performance standards for commercial buildings. States should set standards tight enough to spur innovation in their building industries.

13. Congress should appropriate and the White House should approve for the DOE Office of Science funds that are consistent with the spending profiles specified in the 2005 Energy Policy Act and the 2007 America COMPETES Act. Congress should exercise its oversight responsibility to ensure that basic research related to energy efficiency receives adequate attention in the selection of Energy Frontiers Research Centers.

14. To meet the out-year technology goals this report sets for energy efficiency, DOE must take steps to fold long-term applied research into its scientific programming in a more serious way than it currently does. The department has several options. It can charge the Office of Science with the responsibility and provide the necessary budget, but if it does so, it must protect the culture and budgets of its current basic research programs. It can designate the Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Office (EERE) with the responsibility and augment its budget for that purpose, but in that case, DOE must be careful not to allow short-term activities to continue to diminish long-term opportunities. The department can also create a new structure to support long-term applied research or adapt Advanced Research Projects Agency - Energy (ARPA-E), which was established by the America COMPETES Act.

15. The Department of Energy should fully comply with the 2005 Energy Policy Act mandate to improve the coordination between its basic and applied research activities. Congressional oversight committees should ensure that DOE fulfills its obligation.

16. ARPA-E, if funded, needs to have its purposes better defined. Its time horizon must be clarified, and the coupling to its ultimate customer, the private sector, needs better focus. This report takes no position on whether ARPA-E should be funded.

17. Long-term basic and applied research in energy efficiency should be pursued aggressively. In the case of transportation, the opportunities often point up the close connections between basic and applied research and underscore the need for close coordination of the two activities. In the case of buildings, the fragmented nature of the industry and EERE's focus on near-term research and demonstration programs have led to a serious lack of long-range applied R&D, a deficiency that needs to be rectified.

I would like to see a transition from gas powered vehicles to all electric, but we could certainly get much better efficiency using existing technology by simply building smaller and lighter vehicles. If we can do that without compromising on safety and affordability it makes sense.

Not sure I'd want to be driving a light-weight vehicle and get into an arguement with a woozy truck driver on amphetimines pushing an over-loaded double truck at 80mph-plus on I-95. What is the solution? Separate roads for trucks? Better freight-carrying railroads for long-distance to eliminate long-distance trucking? So much of our goods are delivered by truck it would be impossible to force a reduction in the weight of trucks.